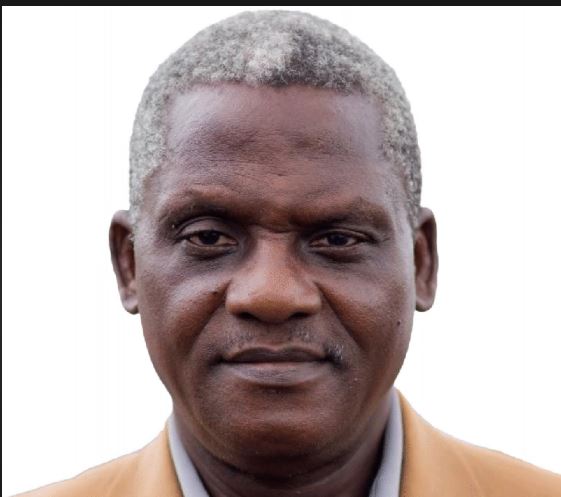

Restorative justice key to Nigeria’s broken system — Olujobi,

Pastor Hezekiah Olujobi is the Executive Director of the Centre for Justice, Mercy and Reconciliation, CJMR and has spent the past two decades fighting for the rights of wrongly convicted inmates and pre-trial detainees.

In this interview, he speaks on the root causes of wrongful convictions in Nigeria, systemic barriers to justice, the transformative power of restorative justice, and the tireless efforts of his organisation in securing freedom for the innocent.

Tell us more about your organisation

Over the years, the Centre for Justice, Mercy and Reconciliation, CJMR, has been actively engaged in various initiatives aimed at promoting justice, human rights, and reconciliation across South-West Nigeria’s custodial centers. Our key activities include prison visitation, casework intervention, investigations, legal advocacy, restorative justice, access to justice, and reintegration through our Halfway Home.

When we believe someone is wrongly convicted, we investigate, compile reports, and connect them with pro bono lawyers. We support legal processes through transport fares, document duplication, and case follow-up. If the courts fail, we proceed to the appellate level or seek mercy from state governors.

We have facilitated the release of 26 individuals on death row and over 1,000 detainees. Over 500 former inmates have been successfully reintegrated through our Halfway Home.

Your organisation appears to focus more on mercy and reconciliation. In your experience, what would you say are the most common causes of wrongful convictions in Nigeria?

In our experience at CJMR, some of the common causes of wrongful convictions in Nigeria include coerced confessions and torture. Many innocent individuals are forced to confess to crimes they did not commit due to physical and psychological torture by law enforcement agencies. These confessions are often used as primary evidence in court. Some Nigerian police are so clever and good at writing confessional statements, it’s like writing a fiction story.

Fabricated stories and false allegations are also contributing factors. There are instances where false accusations are made, sometimes driven by personal vendettas, misunderstandings, or corrupt motives, leading to wrongful arrests and convictions. When two friends or neighbours have misunderstanding, they often resolve it by using the police as a means of revenge.

There was a case of two neighbours in a Muslim community, attending the same mosque. The woman set up the son of the man for a case of armed robbery because he refused to befriend her. The wealthy woman, a single mother, masterminded the setup using another neighbour as a cover-up. We uncovered the truth of the matter after several failed attempts by others. When we stepped in, we resolved the matter. The case was withdrawn from court, and the boy was set free after three years in detention.

Inadequate legal representation is another factor. Many accused persons, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds, lack access to competent legal counsel, which severely hampers their ability to defend themselves effectively. Having taken details of their stories with proper briefing through our report, they are defended effectively.

At times, courts rely heavily on questionable evidence such as coerced confessions without sufficient corroboration, and dissenting opinions that could have prevented wrongful convictions are ignored. These factors combined create an environment where justice is compromised, and innocent people suffer unjustly. Addressing these root causes is essential to reforming the system and preventing future miscarriages of justice.

Access to justice is a major concern, especially for the poor. What systemic barriers have you observed that deny ordinary Nigerians fair hearing or legal representation?

Access to justice remains a significant challenge for many ordinary Nigerians, particularly the poor and marginalised. From our work at CJMR, several systemic barriers stand out.

For instance, legal representation can be prohibitively expensive for many Nigerians. Without adequate funds, accused persons often cannot afford competent lawyers and must rely on overburdened public defenders or self-representation, which puts them at a severe disadvantage. There is also a shortage of accessible and effective legal aid services, especially outside major urban centers. This limits the ability of indigent defendants to obtain timely and quality legal assistance.

The criminal justice system is often slow, with cases dragging on for years due to backlogs, inefficient court procedures, and administrative bottlenecks. This prolongs detention and denies timely resolution. Sometimes when judges go on their annual leave, suspects have no option but to wait until they resume. Other engagements of judges, such as election petition duties, also play a role in the delay of cases.

Poorly conducted investigations often lead to weak or fabricated evidence, yet the accused may lack the resources to challenge this effectively in court. These systemic barriers collectively deny many Nigerians a fair hearing and contribute to wrongful convictions and prolonged unjust detentions. Addressing these issues requires comprehensive reforms, increased funding for legal aid, judicial capacity- building, and public legal education.

The slow pace of trials is a recurring problem in our courts. In your view, what practical reforms can reduce pre-trial detention and case backlog?

One of the most persistent challenges facing Nigeria’s criminal justice system is the slow pace of trials, which continues to result in prolonged pre-trial detentions and a growing backlog of cases. For organisations like CJMR, which works closely with individuals entangled in the criminal justice process, this is not just a policy concern—it is a daily reality that undermines justice and fairness.

To address this systemic issue, CJMR believes that a combination of practical reforms is urgently needed. One of the most impactful steps would be the introduction of modern case tracking and management systems. By digitising and monitoring the progress of cases, such systems could help courts enforce clear timelines, discourage unnecessary adjournments, and improve overall efficiency.

Equally important is the need to strengthen the judiciary’s capacity. Many courts are simply overwhelmed by the volume of cases they must handle. Recruiting and training more judges, magistrates, and court staff would go a long way in easing this burden and ensuring that justice is neither delayed nor denied.

In addition to bolstering human resources, there should be a greater reliance on alternative mechanisms for resolving disputes. For example, plea bargaining and mediation can be highly effective in suitable cases, sparing the courts from lengthy trials while delivering timely resolutions for all parties involved.

Another critical area for reform is the bail system. Far too often, individuals charged with non-violent or minor offences are kept in pre-trial detention for months—or even years—simply because they cannot meet the terms of bail. Reforming these procedures to prioritise non-custodial measures and ensure that bail is not needlessly restrictive, would significantly reduce the number of people awaiting trial in overcrowded prisons.

Furthermore, the investigative and prosecutorial process must be improved. Delays caused by poor or incomplete investigations are all too common. Ensuring that cases are thoroughly and promptly prepared before reaching the courts would eliminate many of these bottlenecks.

You’ve advocated for restorative justice in the past. Can you explain how this model could work in Nigeria, especially in non-violent or minor offences?

Restorative justice is a model that focuses on repairing the harm caused by criminal behavior through inclusive processes that engage victims, offenders, and the community. In the Nigerian context, especially for non-violent or minor offences, restorative justice could offer several benefits and practical applications.

Through our intervention, we have promoted restorative justice between victims and offenders even in capital offences such as armed robbery and murder. We resolved the cases outside court, and as a result, helped both the victim and the offender find true healing. I have written a book on these efforts, though it is yet to be published. It’s titled: Their Hurts and Unforgettable Stories.

Facilitated meetings between victims and offenders allow for acknowledgment of harm, expression of remorse, and agreement on how to make amends. This process can promote healing and reduce feelings of resentment or desire for revenge. By focusing on accountability and making amends, restorative justice supports the offender’s reintegration into society, reducing recidivism and promoting social harmony. This is why we established a Halfway Home for effective rehabilitation and reintegration. The home has produced over 500 beneficiaries.

Restorative processes are generally quicker and less costly than formal court proceedings, helping to alleviate case backlogs and reduce the burden on the criminal justice system. Incorporating indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms and respecting local customs can enhance the legitimacy and acceptance of restorative justice in Nigerian communities.

Restorative justice is not explicitly mentioned in the Nigerian Constitution, but it is referenced in the Nigerian Correctional Service Act, 2019, Section 4, which outlines the functions of the Service, including rehabilitation and reintegration of offenders. This is what we have been doing. But to initiate victim-offender mediation, an independent initiative is required. There is a need to create more awareness about restorative justice in Nigeria as a viable alternative to traditional punitive measures.

We’ve seen cases where inmates spend decades in prison without trial. How is your Centre intervening in such cases, and how do the authorities respond to your findings?

At CJMR, we are deeply committed to addressing the plight of inmates who have spent decades in prison without trial. Our interventions in such cases typically involve the following steps: We work closely with prison authorities, families, and other stakeholders to identify inmates who have been detained for prolonged periods without trial. We document their cases meticulously, gathering relevant information and legal records.

Many authorities have been receptive to our findings and interventions, recognising the human rights implications of prolonged detention. The Boards of Mercy and governors have, in several instances, granted amnesty or pardons to inmates identified through our advocacy, leading to their release.

Some judicial officers have shown willingness to prioritize cases flagged by our Centre, helping to reduce delays. However, challenges remain, including bureaucratic inertia, resource constraints, and occasional resistance within parts of the system. But with our consistency, we have been attended to at last.

Overall, our persistent engagement and evidence-based advocacy have led to tangible successes in securing justice and freedom for many long-detained inmates. We continue to collaborate with all stakeholders to promote systemic reforms that prevent such injustices from recurring.

There’s a growing conversation about decriminalizing petty offences. Do you support this, and what impact would such reform have on the prison population?

That has been part of our goals. We have successfully addressed that issue in Oyo State. Cases of dumping refuse in a prohibited area or sending underage children to prison for such offenses—we visited the customary courts that were doing this to stop them.

Our investigation revealed some of these homeless boys and girls were from broken homes and not being treated well at home. They had to fend for themselves. They would go to the local food canteens to help pack their refuse and dispose of it in illegal dumping grounds. We strongly support the decriminalisation of petty offenses. This reform can have a profound positive impact on Nigeria’s prison population and broader justice system.

We engaged with the customary courts responsible for sentencing these children and successfully advocated for a stop to sending underage offenders to prison. Instead, we promoted more compassionate and rehabilitative approaches that consider the socio-economic realities of these children.

Decriminalising petty offenses aligns with restorative justice principles and human rights standards. Our work in Oyo State demonstrates that with targeted advocacy and collaboration with judicial and community stakeholders, meaningful reforms are possible. We encourage broader adoption of such reforms across Nigeria to create a more just, humane, and effective criminal justice system.

What are the major challenges you face in delivering your mission?

First, resources are limited. We rely on donations and goodwill to support legal fees, transportation, and documentation. Second, we face resistance from parts of the justice system unwilling to embrace reform. Judicial inertia and bureaucratic red tape also slow progress.

Third, there is a gap in public awareness. Many Nigerians do not know their rights, and public sympathy for detainees is often low.

Nonetheless, we are undeterred. We continue to work with partners and draw the attention of Attorneys General to deserving cases. We will not rest until every innocent man and woman behind bars gets a fair hearing.

The post Restorative justice key to Nigeria’s broken system — Olujobi appeared first on Vanguard News.

,

Pastor Hezekiah Olujobi is the Executive Director of the Centre for Justice, Mercy and Reconciliation, CJMR and has spent the past two decades fighting for the rights of wrongly convicted inmates and pre-trial detainees.

The post Restorative justice key to Nigeria’s broken system — Olujobi appeared first on Vanguard News.

, , Nwafor, {authorlink},, , Vanguard News, August 7, 2025, 12:37 am